Reference: Ian Sommerville, Software Engineering, 10 ed., Chapter 11

Note: The information provided here is an overview of the course notes provided by Dr. Stan Kurkovsky for Software Engineering

The big picture

In general, software customers expect all software to be dependable. However, for non-critical applications, they may be willing to accept some system failures. Some applications (critical systems) have very high reliability requirements and special software engineering techniques may be used to achieve this.

Reliability terminology

| Term | Description |

| Human error or mistake | Human behavior that results in the introduction of faults into a system. |

| System fault | A characteristic of a software system that can lead to a system error. |

| System error | An erroneous system state that can lead to system behavior that is unexpected by system users. |

| System failure | An event that occurs at some point in time when the system does not deliver a service as expected by its users. |

Failures are a usually a result of system errors that are derived from faults in the system. However, faults do not necessarily result in system errors if the erroneous system state is transient and can be 'corrected' before an error arises. Errors do not necessarily lead to system failures if the error is corrected by built-in error detection and recovery mechanism.

Fault management strategies to achieve reliability:

- Fault avoidance

- Development techniques are used that either minimize the possibility of mistakes or trap mistakes before they result in the introduction of system faults.

- Fault detection and removal

- Verification and validation techniques that increase the probability of detecting and correcting errors before the system goes into service are used.

- Fault tolerance

- Run-time techniques are used to ensure that system faults do not result in system errors and/or that system errors do not lead to system failures.

Availability and reliability

Reliability is the probability of failure-free system operation over a specified time in a given environment for a given purpose. Availability is the probability that a system, at a point in time, will be operational and able to deliver the requested services. Both of these attributes can be expressed quantitatively e.g. availability of 0.999 means that the system is up and running for 99.9% of the time.

The formal definition of reliability does not always reflect the user's perception of a system's reliability. Reliability can only be defined formally with respect to a system specification i.e. a failure is a deviation from a specification. Users don't read specifications and don't know how the system is supposed to behave; therefore, perceived reliability is more important in practice.

Availability is usually expressed as a percentage of the time that the system is available to deliver services e.g. 99.95%. However, this does not take into account two factors:

- The number of users affected by the service outage. Loss of service in the middle of the night is less important for many systems than loss of service during peak usage periods.

- The length of the outage. The longer the outage, the more the disruption. Several short outages are less likely to be disruptive than 1 long outage. Long repair times are a particular problem.

Removing X% of the faults in a system will not necessarily improve the reliability by X%. Program defects may be in rarely executed sections of the code so may never be encountered by users. Removing these does not affect the perceived reliability. Users adapt their behavior to avoid system features that may fail for them. A program with known faults may therefore still be perceived as reliable by its users.

Reliability requirements

Functional reliability requirements define system and software functions that avoid, detect or tolerate faults in the software and so ensure that these faults do not lead to system failure.

Reliability is a measurable system attribute so non-functional reliability requirements may be specified quantitatively. These define the number of failures that are acceptable during normal use of the system or the time in which the system must be available. Functional reliability requirements define system and software functions that avoid, detect or tolerate faults in the software and so ensure that these faults do not lead to system failure. Software reliability requirements may also be included to cope with hardware failure or operator error.

Reliability metrics are units of measurement of system reliability. System reliability is measured by counting the number of operational failures and, where appropriate, relating these to the demands made on the system and the time that the system has been operational. Metrics include:

- Probability of failure on demand (POFOD). The probability that the system will fail when a service request is made. Useful when demands for service are intermittent and relatively infrequent.

- Rate of occurrence of failures (ROCOF). Reflects the rate of occurrence of failure in the system. Relevant for systems where the system has to process a large number of similar requests in a short time. Mean time to failure (MTTF) is the reciprocal of ROCOF.

- Availability (AVAIL). Measure of the fraction of the time that the system is available for use. Takes repair and restart time into account. Relevant for non-stop, continuously running systems.

Non-functional reliability requirements are specifications of the required reliability and availability of a system using one of the reliability metrics (POFOD, ROCOF or AVAIL). Quantitative reliability and availability specification has been used for many years in safety-critical systems but is uncommon for business critical systems. However, as more and more companies demand 24/7 service from their systems, it makes sense for them to be precise about their reliability and availability expectations.

Functional reliability requirements specify the faults to be detected and the actions to be taken to ensure that these faults do not lead to system failures.

- Checking requirements that identify checks to ensure that incorrect data is detected before it leads to a failure.

- Recovery requirements that are geared to help the system recover after a failure has occurred.

- Redundancy requirements that specify redundant features of the system to be included.

- Process requirements for reliability which specify the development process to be used may also be included.

Fault tolerance

In critical situations, software systems must be fault tolerant. Fault tolerance is required where there are high availability requirements or where system failure costs are very high. Fault tolerance means that the system can continue in operation in spite of software failure. Even if the system has been proved to conform to its specification, it must also be fault tolerant as there may be specification errors or the validation may be incorrect.

Fault-tolerant systems architectures are used in situations where fault tolerance is essential. These architectures are generally all based on redundancy and diversity. Examples of situations where dependable architectures are used:

- Flight control systems, where system failure could threaten the safety of passengers;

- Reactor systems where failure of a control system could lead to a chemical or nuclear emergency;

- Telecommunication systems, where there is a need for 24/7 availability.

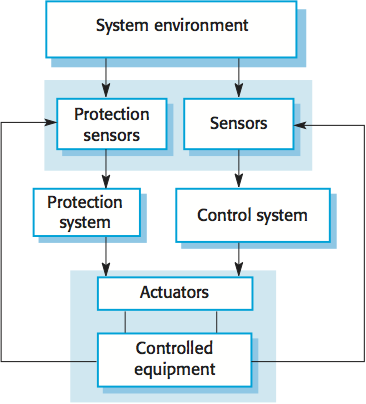

Protection system is a specialized system that is associated with some other control system, which can take emergency action if a failure occurs, e.g. a system to stop a train if it passes a red light, or a system to shut down a reactor if temperature/pressure are too high. Protection systems independently monitor the controlled system and the environment. If a problem is detected, it issues commands to take emergency action to shut down the system and avoid a catastrophe. Protection systems are redundant because they include monitoring and control capabilities that replicate those in the control software. Protection systems should be diverse and use different technology from the control software. They are simpler than the control system so more effort can be expended in validation and dependability assurance. Aim is to ensure that there is a low probability of failure on demand for the protection system.

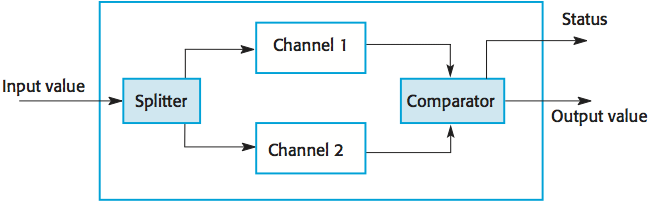

Self-monitoring architecture is a multi-channel architectures where the system monitors its own operations and takes action if inconsistencies are detected. The same computation is carried out on each channel and the results are compared. If the results are identical and are produced at the same time, then it is assumed that the system is operating correctly. If the results are different, then a failure is assumed and a failure exception is raised. Hardware in each channel has to be diverse so that common mode hardware failure will not lead to each channel producing the same results. Software in each channel must also be diverse, otherwise the same software error would affect each channel. If high-availability is required, you may use several self-checking systems in parallel. This is the approach used in the Airbus family of aircraft for their flight control systems.

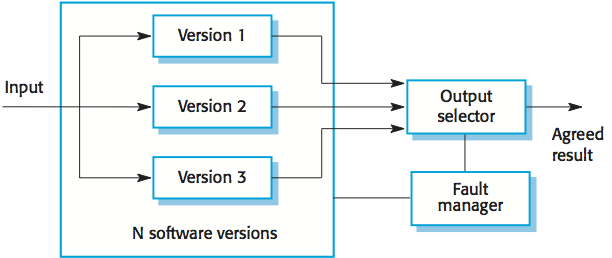

N-version programming involves multiple versions of a software system to carry out computations at the same time. There should be an odd number of computers involved, typically 3. The results are compared using a voting system and the majority result is taken to be the correct result. Approach derived from the notion of triple-modular redundancy, as used in hardware systems.

Hardware fault tolerance depends on triple-modular redundancy (TMR). There are three replicated identical components that receive the same input and whose outputs are compared. If one output is different, it is ignored and component failure is assumed. Based on most faults resulting from component failures rather than design faults and a low probability of simultaneous component failure.

Programming for reliability

Good programming practices can be adopted that help reduce the incidence of program faults. These programming practices support fault avoidance, detection, and tolerance.

- Limit the visibility of information in a program

- Program components should only be allowed access to data that they need for their implementation. This means that accidental corruption of parts of the program state by these components is impossible. You can control visibility by using abstract data types where the data representation is private and you only allow access to the data through predefined operations such as get () and put ().

- Check all inputs for validity

- All program take inputs from their environment and make assumptions about these inputs. However, program specifications rarely define what to do if an input is not consistent with these assumptions. Consequently, many programs behave unpredictably when presented with unusual inputs and, sometimes, these are threats to the security of the system. Consequently, you should always check inputs before processing against the assumptions made about these inputs.

- Provide a handler for all exceptions

- A program exception is an error or some unexpected event such as a power failure. Exception handling constructs allow for such events to be handled without the need for continual status checking to detect exceptions. Using normal control constructs to detect exceptions needs many additional statements to be added to the program. This adds a significant overhead and is potentially error-prone.

- Minimize the use of error-prone constructs

- Program faults are usually a consequence of human error because programmers lose track of the relationships between the different parts of the system This is exacerbated by error-prone constructs in programming languages that are inherently complex or that don't check for mistakes when they could do so. Therefore, when programming, you should try to avoid or at least minimize the use of these error-prone constructs.

- Error-prone constructs:

- Unconditional branch (goto) statements

- Floating-point numbers (inherently imprecise, which may lead to invalid comparisons)

- Pointers

- Dynamic memory allocation

- Parallelism (can result in subtle timing errors because of unforeseen interaction between parallel processes)

- Recursion (can cause memory overflow as the program stack fills up)

- Interrupts (can cause a critical operation to be terminated and make a program difficult to understand)

- Inheritance (code is not localized, which may result in unexpected behavior when changes are made and problems of understanding the code)

- Aliasing (using more than 1 name to refer to the same state variable)

- Unbounded arrays (may result in buffer overflow)

- Default input processing (if the default action is to transfer control elsewhere in the program, incorrect or deliberately malicious input can then trigger a program failure)

- Provide restart capabilities

- For systems that involve long transactions or user interactions, you should always provide a restart capability that allows the system to restart after failure without users having to redo everything that they have done.

- Check array bounds

- In some programming languages, such as C, it is possible to address a memory location outside of the range allowed for in an array declaration. This leads to the well-known 'bounded buffer' vulnerability where attackers write executable code into memory by deliberately writing beyond the top element in an array. If your language does not include bound checking, you should therefore always check that an array access is within the bounds of the array.

- Include timeouts when calling external components

- In a distributed system, failure of a remote computer can be 'silent' so that programs expecting a service from that computer may never receive that service or any indication that there has been a failure. To avoid this, you should always include timeouts on all calls to external components. After a defined time period has elapsed without a response, your system should then assume failure and take whatever actions are required to recover from this.

- Name all constants that represent real-world values

- Always give constants that reflect real-world values (such as tax rates) names rather than using their numeric values and always refer to them by name You are less likely to make mistakes and type the wrong value when you are using a name rather than a value. This means that when these 'constants' change (for sure, they are not really constant), then you only have to make the change in one place in your program.